Prevalence of Somatic BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutations in Ovarian Cancer among Filipinos using Next Generation Sequencing

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.21141/PJP.2023.05Keywords:

ovarian cancer, BRCA somatic mutations, next generation sequencingAbstract

Introduction. Ovarian cancer is one of the leading causes of mortality in women. In 2020, 5,395 (6.2%) of diagnosed malignancies in females were ovarian in origin. It also ranked second among gynecologic malignancies after cervical cancer. The prevalence in Asian /Pacific women is 9.2 per 100,000 population. Increased mortality and poor prognosis in ovarian cancer is caused by asymptomatic growth and delayed or absent symptoms for which about 70% of women have advanced stage (III/IV) by the time of diagnosis. The most commonly associated gene mutations are Breast Cancer gene 1 (BRCA1) which is identified in chromosome 17q21 and Breast Cancer gene 2 (BRCA2) identified in chromosome 13. Both proteins function in the double strand DNA break repair pathway especially in the large framework repair molecules. Olaparib is a first-line drug used in the management of ovarian cancer. It targets affected cells by inhibition of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) activity which induces synthetic lethality in mutated BRCA1/2 cancers by selectively targeting tumor cells that fail to repair DNA double strand breaks (DSBs).

Objectives. The general objective of this study is to determine the prevalence of pathogenic somatic mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 among patients diagnosed of having ovarian cancer. The specific objectives are: 1) to characterize the identified variants into benign/no pathogenic variant identified, variant of uncertain significance (VUS), and pathogenic and 2) to determine the relationship of specific mutations detected with histomorphologic findings and clinical attributes.

Methodology. Ovarian cancer tissues available in St. Luke’s Medical Center Human Cancer Biobank and formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks diagnosed as ovarian cancer from year 2016 to 2020 were included. Determination of the prevalence of somatic BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations using next generation sequencing.

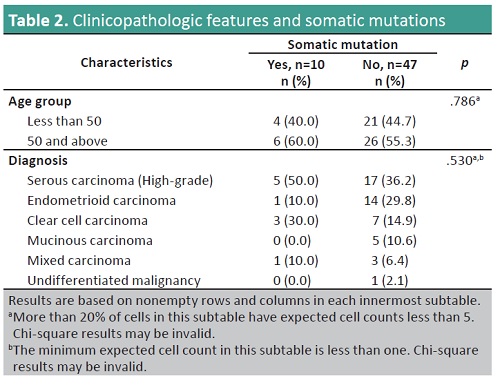

Results. A total of 60 samples were processed, three samples were excluded from the analysis due to inadequate number of cells. In the remaining 57 samples diagnosed ovarian tumors, pathogenic BRCA1/2 variants were identified in 10 (17.5%) samples. Among the BRCA1/2 positive samples, 3 (5.3%) BRCA1 and 7 (12.3%) BRCA2 somatic mutations were identified.

Conclusions. In conclusion, identification of specific BRCA1/2 mutations in FFPE samples with the use next generation sequencing plays a big role in the management of ovarian cancer particularly with the use of targeted therapies such as olaparib. The use of this drug could provide a longer disease-free survival for these patients. Furthermore, we recommend that women diagnosed with ovarian cancer should be subjected to genetic testing regardless of the histologic subtypes or clinical features. Lastly, genetic testing should be done along with proper genetic counselling especially to patients who are susceptible to these mutations.

Downloads

References

International Agency for Research on Cancer. World Health Organization. The Global Cancer Observatory; 2020. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/608-philippines-fact-sheets.pdf.

Momenimovahed Z, Tiznobaik A, Taheri S, Salehiniya H. Ovarian cancer in the world: epidemiology and risk factors. Int J Womens Health. 2019;11:287-99. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31118829. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6500433. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S197604. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S197604

Natanzon Y, Goode EL, Cunningham JM. Epigenetics in ovarian cancer. Seminars Cancer Biol. 2018;51:160-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28782606. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5976557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.08.003. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.08.003

Ramus SJ, Gayther SA. The contribution of BRCA1 and BRCA2 to ovarian cancer. Mol Oncol. 2009;3(2):138-50. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19383375. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5527889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molonc.2009.02.001. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molonc.2009.02.001

Goodheart MJ, Rose SL, Hattermann-Zogg M, Smith BJ, De Young BR, Buller RE. BRCA2 alteration is important in clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Clin Genet. 2009;76(2):161-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19656163. https;//doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01207.x. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01207.x

Koczkowska M, Zuk M, Gorczynski A, et al. Detection of somatic BRCA1/2 mutations in ovarian cancer - next-generation sequencing analysis of 100 cases. Cancer Med. 2016;5(7):1640–6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27167707. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4867663. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.748. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.748

Hennessy BT, Timms KM, Carey MS, et al. Somatic mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 could expand the number of patients that benefit from poly (ADP ribose) polymerase inhibitors in ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010; 28(22):3570–6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20606085. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2917312. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.27.2997. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.27.2997

Faraoni I, Graziani G. Role of BRCA mutations in cancer treatment with poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors. Cancers (Basel). 2018;10(12):487. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30518089. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6316750. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers10120487. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers10120487

George A, Banerjee S, Kaye S. Olaparib and somatic BRCA mutations. Oncotarget. 2017;8(27): 43598–9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28611314. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5546426. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.18419. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.18419

Nalley C. Benefit of olaparib for brca-mutated advanced ovarian cancer, Oncology Times. 2020;42(22):23,30. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.COT.0000723552.86174.ff DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.COT.0000723552.86174.ff

Montemorano L, Lightfoot MD, Bixel K. Role of olaparib as maintenance treatment for ovarian cancer: the evidence to date. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:11497-506. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31920338. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6938196. https://doi.org/10.2147/OTT.S195552. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2147/OTT.S195552

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2023 PJP

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The Philippine Journal of Pathology is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on works made open access at http://philippinejournalofpathology.org